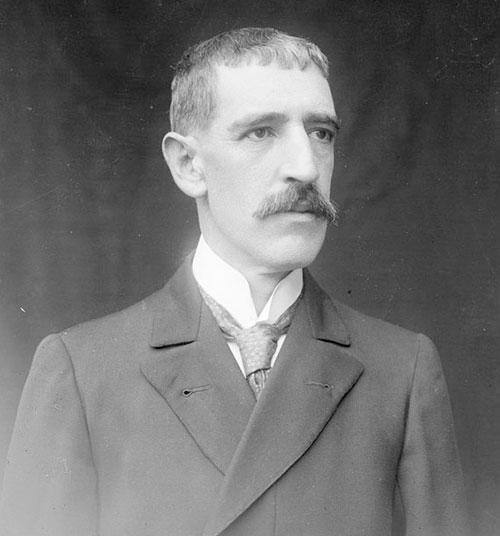

Octavio Cordero Palacios (Santa Rosa, Azuay, May 3, 1870 – Cuenca, December 17, 1930) was an Ecuadorian writer, poet, playwright, mathematician, lawyer, professor, and inventor. Known for his early literary works such as Gazul (1890) and Los Hijos de Atahualpa (1891), he was also a prolific translator, famously rendering Edgar Allan Poe’s The Raven into Spanish. A graduate of the Universidad de Cuenca, he practiced law and served as a judge while pursuing his intellectual passions, which included pioneering inventions like the Clave Poligráfica, a mechanical translation device. Today, the town where he was born bears his name.

Early Life and Education

Octavio Cordero Palacios was born on May 3, 1870, in the village of Santa Rosa, Azuay Province, Ecuador. His birth was somewhat accidental, occurring in a modest hut while his mother, Rosa Palacios Alvear, was en route to a nearby church. His father, Vicente Cordero Crespo, was a notable poet and conservative journalist who edited the magazine El Criterio. Raised in an intellectual environment, Cordero began his education in 1877 at a school in Cañar before moving to Cuenca. There, he attended the San José School of the Christian Brothers and completed his secondary education at the Colegio San Luis, where he developed an interest in classical humanities, including Latin and Greek. Cordero was an avid learner of multiple languages, acquiring proficiency in reading English and French.

Literary Career

Cordero’s intellectual journey began early, marked by his passion for writing. At the age of 20, he debuted his first play, Gazul, in 1890. This three-act drama, set in Persia at the time of the First Crusade, was heavily influenced by his mentor, Father Julio Matovelle. Following this, he wrote Los Hijos de Atahualpa and Los Borrachos in 1892. Although the latter received mixed reviews, with prominent critic Manuel J. Calle deeming it disjointed, Cordero was not deterred. His focus shifted to translations, producing Rapsodias Clásicas, translations of works by Virgil and Horace. His most celebrated translation was Edgar Allan Poe’s The Raven, which was widely praised for its accuracy and poetic form.

Throughout his life, Cordero’s literary output remained prolific. Notable later works include Vida de Abdón Calderón (1916), an account of the Ecuadorian independence hero, and De Potencia a Potencia (1922), a historical essay on the conflict between President Gabriel García Moreno and the Governor of Azuay, Manuel Vega. His work El quichua y el Cañari (1923) was a pioneering study of the Quechua and Cañari languages, earning him the Palma de Oro.

Professional Life and Inventions

In 1890, Cordero graduated with a doctorate in law from the Universidad de Cuenca. He practiced as a lawyer and served for a decade as a judge on the Superior Court of Azuay. His career in public service also included roles as a senator for Azuay from 1916 to 1918 and as Inspector General for the Sibambe-Cuenca railway, where he made significant contributions to the improvement of the rail network.

Cordero was not only a man of letters but also an inventor. In 1902, he created the Clave Poligráfica or Metaglota, a mechanical device designed to translate words between languages. This early translation machine, considered a marvel of engineering at the time, was exhibited posthumously in Quito in 1936. Cordero also invented an advanced abacus capable of calculating square roots and authored a “Trigonometría en Verso,” a mathematical textbook written in verse.

Educational Contributions

In addition to his literary and legal pursuits, Octavio Cordero Palacios made significant contributions to education and philosophy in Ecuador. As a professor at the Colegio Benigno Malo and the Universidad de Cuenca, he taught subjects such as literature, philosophy, and civil engineering. His intellectual curiosity spanned diverse fields, and he was known for blending scientific thought with poetic expression, as seen in his Trigonometría en Verso—a unique approach to teaching complex mathematical concepts through verse. He was also instrumental in bringing classical knowledge to Ecuadorian education, translating and disseminating works of ancient philosophers and poets, such as Horace and Virgil. Through his teachings, publications, and translations, Cordero contributed to fostering a generation of critical thinkers in Ecuador, influencing the intellectual landscape of Cuenca in the early 20th century.

Military Contributions

During the 1910 conflict with Peru, Cordero demonstrated his versatility by joining the military reserves, where he attained the rank of Major. Appointed Chief Engineer of the First Southern Division, he created a topographic map of Ecuador’s southern border. He also taught courses on planimetry, altimetry, and civil engineering at the Universidad de Cuenca.

Personal Life

Cordero married his second cousin, Victoria Crespo Astudillo, with whom he had several children. Despite his many intellectual and professional achievements, Cordero lived much of his later life in poverty. He faced financial difficulties, which may have hindered the completion and publication of some of his planned works.

Death and Legacy

In his final days, suffering from cirrhosis, Cordero remained philosophical about death. He predicted that he would die on December 17, 1930, exactly 100 years after the death of Simón Bolívar—a prophecy that proved accurate. He passed away at 6:30 p.m., reciting the Ecuadorian national anthem as his final words. He requested that instead of his name, the following verse be inscribed on his tombstone:

“If struck, struck, and struck by God’s august hand,

What to do? Fall upon the earth, bow the head,

Receive in silence—lightning bolt after lightning bolt,

The full fire and fury of the sovereign thunder.”

He was laid to rest in the Ilustre Mausoleo de Personajes at the Municipal Cemetery of Cuenca.

Cordero’s legacy endures in various forms. The rural parish of Octavio Cordero Palacios in Cuenca was named in his honor, as was a school in Déleg. His life and contributions to Ecuadorian literature, law, and education continue to be celebrated as emblematic of the intellectual vibrancy of his era.

Works

- Gazul (1890), read it for free: part 1, part 2, part 3, part 4. Read an English translation here.

- Los Hijos de Atahualpa (1891)

- Los Borrachos (1892)

- Vida de Abdón Calderón (1916), a biography of the legendary young hero of the Battle of Pichincha. Read it for free here.

- De Potencia a Potencia (1922)

- El Quechua y el Cañari (1923), a philological study of Quechua and Cañari languages, with a Cañari Dictionary, which was awarded “La Palma de Oro” Prize

- El Azuay Histórico

- Protomebamba y sus Crónicas Documentadas para la Historia de Cuenca (1924)

- La Poesía de Ciencia (1929)

Translations

- El Cuervo, a Spanish translation of Edgar Allan Poe’s The Raven.

- Rapsodias Clásicas, a Spanish translation of works by Virgil and Horace.

References

- Wikipedia, “Octavio Cordero Palacios.” Retrieved on October 5, 2024. Click to view.

- Diccionario Biográfico Ecuador, “Cordero Palacios, Octavio.” Retrieved on October 5, 2024. Click to view.

- EcuRed, “Octavio Cordero Palacios.” Retrieved on October 5, 2024. Click to view.

- Enciclopedia del Ecuador, “Dr. Octavio Cordero Palacios.” Retrieved on October 5, 2024. Click to view.

- Rodolfo Pérez Pimentel, “Cordero Palacios, Octavio.” Retrieved on October 5, 2024. Click to view.