Medardo Ángel Silva Rodas (Guayaquil, June 8, 1898 – Guayaquil, June 10, 1919) was an Ecuadorian poet, writer, and journalist, known as one of the most significant members of the Generación Decapitada (Decapitated Generation), a group of modernist poets in early 20th-century Ecuador. His work, heavily influenced by French symbolism and the modernist movement led by Rubén Darío, explored themes of love, melancholy, and death. Silva published his poetry in his collection El árbol del bien y del mal (1918) and gained national recognition with his poem “El alma en los labios,” later made famous as a song by Julio Jaramillo. His tragic death at 21, widely believed to be a suicide, remains shrouded in mystery, further enshrining his place in Ecuadorian literary history.

Early Life and Education

Medardo Ángel Silva was born on June 8, 1898, in Guayaquil, Ecuador, into a family with a deep appreciation for music and the arts. His father, Enrique Silva Valdés, was a mulatto pianist and piano tuner of modest means, known for his musical talent but also marked by the hardships of poverty. Silva’s mother, Mariana Rodas Moreira, a woman of trigueña complexion, was not only a graceful and elegant figure but also a poet in her own right. Her poetic sensibilities would deeply influence Silva’s emotional development and intellectual curiosity. Despite their lower-middle-class status, Silva’s parents were respected for their cultural refinement and education, though the family was far from financially secure.

Tragedy struck Silva’s life early when his father died of tuberculosis in 1902, leaving the young Medardo, then just three years old, to be raised by his mother in an increasingly precarious financial situation. The loss of his father and the ensuing instability likely played a key role in shaping Silva’s melancholic outlook on life, a trait that would later be a hallmark of his poetry. He and his mother lived in a modest wooden house near the Juan Pablo Arenas alley, a place he would later describe as filled with the presence of funerals and the passing of hearses—imagery that seemed to foreshadow his later preoccupation with death.

Silva’s childhood was marked by a rich inner life. He was a sensitive, introspective boy who found solace in books and the arts. From a young age, he showed a precocious interest in literature and music, often reciting poems by Ecuadorian poet José Joaquín de Olmedo and composing his own verses. His mother, recognizing his intellectual potential, nurtured his talents as much as she could. She provided him with sporadic piano lessons, further connecting him to the musical world of his father, but it was Silva’s voracious reading that truly set him apart. By the age of eleven, he was already contributing to local literary magazines.

Silva’s formal education began at the Filantrópica School, a free institution in Guayaquil that was known for educating children from working-class families. Here, Silva excelled in his studies, especially in literature, despite his shyness and introspective nature. He was a diligent student but also known for his dreamy detachment, often lost in his own thoughts. His artistic talents began to manifest early, and he created a handwritten satirical newspaper called El Mosquito, where he documented daily life and his imaginative interpretations of the world around him.

At the age of eleven, Silva was accepted into the prestigious Vicente Rocafuerte High School, one of Ecuador’s leading educational institutions. The school was renowned for its rigorous academic standards and its role in shaping many of Ecuador’s intellectual elites. This was a significant achievement for Silva, as it gave him access to a level of education typically reserved for the children of wealthier families. His time at Vicente Rocafuerte exposed him to the broader world of literature, science, and philosophy, and it was here that his passion for poetry truly began to blossom. He developed an affinity for European Romantic and modernist literature, particularly French works, which he read in translation.

However, Silva’s education was cut short due to financial difficulties. His mother, now a widow struggling to make ends meet, could no longer afford to keep him in school. By his fourth year of secondary education, Silva was forced to leave school to work and support his family. This abrupt end to his formal education was a bitter blow, as Silva had already begun to dream of a life devoted to literature and intellectual pursuits. Nevertheless, he remained undeterred in his quest for knowledge. A committed autodidact, Silva continued to educate himself through voracious reading, particularly of French literature, which he taught himself to read in its original language. His self-directed studies would become a cornerstone of his intellectual and literary development.

As he transitioned into adulthood, Silva worked various jobs, including as a printer’s assistant and later as a teacher. These roles, while necessary for financial survival, allowed him to maintain his connection to the world of literature. Throughout this period, he continued to write poetry and submit his work to local newspapers and literary magazines, slowly gaining recognition in Ecuador’s literary circles. Silva’s early years of hardship and intellectual curiosity deeply informed his later works, which were infused with themes of existential despair, love, and the inevitability of death—preoccupations that he carried with him from his earliest experiences of loss and struggle.

Literary Career

Medardo Ángel Silva’s poetic talent manifested at an early age, driven by his natural affinity for literature and the artistic atmosphere cultivated in his household. Even as a child, he was drawn to the emotional depth of poetry, and by his adolescence, he began seriously composing his own verses. Despite the economic and social challenges he faced, Silva was determined to make a name for himself in Ecuador’s literary circles. His first efforts at getting published were met with rejection due to his youth and lack of connections, but this did not deter him. He continued to submit his work to local newspapers and literary magazines, and by the age of 15, his persistence paid off when his poems were accepted by the magazine Juan Montalvo, a key moment that marked the start of his recognition as a rising literary voice in Guayaquil.

Silva’s early poetry reflected the literary trends of his time, but even in these initial works, his unique voice began to emerge. He was deeply influenced by the modernismo movement, a literary current that sought to break away from traditional forms and embrace new rhythms, symbolism, and emotional intensity. Among his chief inspirations was Nicaraguan poet Rubén Darío, the leading figure of modernismo, whose work combined the musicality of language with a deep exploration of inner emotions and the existential crises of the modern world. Silva found a model in Darío’s ability to blend the sensual with the spiritual, and this became a hallmark of his own style.

Silva’s poetry also drew heavily from French symbolism, particularly the works of Paul Verlaine and Charles Baudelaire. Like the French symbolists, Silva employed imagery that evoked deep emotions, often using dream-like or surreal scenarios to explore complex states of mind. His themes frequently revolved around melancholy, death, and fantasy, reflecting his introspective and troubled nature. Baudelaire’s fascination with beauty and decay, the tension between light and darkness, and Verlaine’s emphasis on musicality in poetry found clear echoes in Silva’s verses. He incorporated these influences into a distinctly Ecuadorean context, blending them with his own personal experiences of loss and alienation. His early poetry was also influenced by Romanticism’s focus on emotion, individualism, and the sublime—yet his version of Romanticism was tinged with the darker tones of existential despair.

By the time he was 19, Silva had already developed a reputation as a precocious talent, and he decided to take control of his literary career by self-publishing his first book, El árbol del bien y del mal (1918). This collection encapsulated the key elements of his poetic style: lyrical richness, a rhythmic musicality that drew from Darío’s influence, and themes of emotional depth, fantasy, and existential reflection. The poems in El árbol del bien y del mal are organized thematically, with sections titled “Las Voces Inefables” (The Ineffable Voices), “Estancias” (Stanzas), “Libro de Amor” (Book of Love), and “Divagaciones Sentimentales” (Sentimental Ramblings). The collection explores the nuances of love, sorrow, and the fleeting nature of beauty, with death often looming as a central motif. In many ways, the book serves as a personal testament to Silva’s inner struggles—his desire to transcend the limitations of his socio-economic background and the constraints of a life that he viewed as tragically short.

Silva’s literary ambitions were not limited to poetry. He was also a gifted prose writer and journalist, with a keen eye for narrative and social commentary. In 1919, he serialized his novella María Jesús in the newspaper El Telégrafo. The novella, a rural love story set in the countryside, reveals a softer, more sentimental side of Silva’s writing, showcasing his ability to weave narrative prose with lyrical expression. María Jesús is believed to be semi-autobiographical, reflecting Silva’s own romantic ideals and his disillusionment with the real world. The novella’s pastoral setting contrasts with the urban environment in which Silva lived, highlighting his yearning for an unattainable, idyllic love.

In addition to his creative writing, Silva was a prolific journalist and essayist. He contributed extensively to El Telégrafo, where he began working as a journalist and literary editor. At El Telégrafo, he was responsible for the “Los jueves literarios” (Literary Thursdays) section, where he promoted new literary voices and introduced readers to modernist trends. His column “Al pasar” (As I Pass By), which he wrote under the pseudonym “Jean D’Agreve,” allowed him to express his more personal and reflective thoughts on a wide range of topics, from literature to social issues. The pseudonym itself was a literary reference to the French author Eugène-Melchior de Vogüé’s novel Jean d’Agrève, a work Silva admired for its exploration of romantic idealism and existential angst—two themes that permeated his own writing. Silva’s choice of this pseudonym reflects his identification with the novel’s protagonist, a tragic figure who ultimately commits suicide, mirroring Silva’s own fascination with death.

Silva’s work was not confined to Ecuador; his essays, short stories, and poems were published in renowned literary magazines across Latin America and Europe, including Nosotros in Buenos Aires and Cervantes in Madrid. These publications brought him international attention, placing him alongside some of the most important literary figures of his time. Despite his youth, Silva’s writing displayed a maturity and complexity that belied his age, earning him respect within Ecuador’s literary circles and beyond.

In 1919, as his literary reputation grew, Silva became a key figure at El Telégrafo. His role as a literary editor gave him a platform to influence Ecuador’s literary scene, and he used this position to champion modernist aesthetics and to critique the social and cultural stagnation he perceived in his country. However, Silva’s success was always overshadowed by his deep sense of alienation and melancholy. His works—whether poetry, prose, or journalism—were infused with an acute awareness of life’s impermanence, the inevitability of death, and the fleeting nature of happiness. These themes, central to his worldview, defined not only his literary output but also the trajectory of his short, tragic life.

Personal Life

Medardo Ángel Silva’s personal life was deeply intertwined with the themes of isolation, longing, and melancholy that permeated his work. Born into a family of limited means, Silva’s economic struggles and his darker complexion set him apart from the more affluent, fair-skinned members of the Generación Decapitada (Decapitated Generation), to which he belonged. Despite his intellectual gifts and his growing reputation in literary circles, Silva’s lower social status and racial background made him feel socially marginalized. These insecurities profoundly affected his sense of identity and contributed to the intense emotional turbulence that marked his personal life. Silva’s feelings of exclusion were exacerbated by his desire to be accepted by the intellectual and social elites of Ecuador, a world that often remained out of reach due to the prejudices of the time.

Silva’s emotional struggles were further complicated by his romantic relationships, which were fraught with intensity and unfulfilled desire. One of the most significant relationships in his life was with Ángela Carrión Vallejo, a young woman who lived in his family’s household. Silva and Carrión had a child together, María Mercedes Cleofé Silva Carrión, born in 1918. The birth of their daughter was a pivotal moment in Silva’s life, but the relationship between Silva and Carrión was not publicized, likely due to societal expectations and the precarious financial situation of both families. Silva’s role as a father was complicated by his ongoing emotional instability and his inability to provide a secure future for his child. María Mercedes, who outlived her father by many decades, would later become a symbolic link to Silva’s personal life, though Silva himself would never be able to fully assume the responsibilities of parenthood before his tragic death.

At the same time, Silva was deeply infatuated with another young woman, Rosa Amada Villegas, a 14-year-old girl who became the muse for one of his most famous poems, El alma en los labios (The Soul on the Lips). Rosa Amada, with her youthful beauty and innocence, represented an idealized version of love for Silva—an unattainable, almost ethereal figure to whom he projected his romantic yearnings. Their relationship was brief, and it appears that Rosa Amada did not reciprocate Silva’s intense emotions with the same depth. In her later years, she reflected on their relationship, recalling how she felt flattered by his attention but also overwhelmed by the depth of his feelings, which were too intense for her to fully understand at such a young age. Rosa Amada would eventually distance herself from Silva, and this unrequited love contributed to the emotional anguish that would define the last years of his life.

Silva’s obsession with Rosa Amada became central to his emotional state, as well as to his literary output. His letters and poems dedicated to her express a mixture of adoration, despair, and a looming sense of doom. El alma en los labios, written just days before his death, captures his feelings of fatalistic love, where he equates the loss of Rosa’s affection with the end of his own life. The poem is laced with suicidal imagery, foreshadowing the tragic events that would soon follow. In it, Silva wrote of his willingness to take his own life if his love for her were ever to be extinguished—a haunting reflection of his state of mind at the time. According to legend, Silva wrote this poem in red ink, as if symbolically linking the act of writing to the spilling of his own blood.

His relationship with Rosa Amada took on mythic proportions in the aftermath of his death, becoming part of the lore surrounding his life and work. The circumstances of Silva’s death on June 10, 1919, remain shrouded in mystery, but it is widely believed that he died by suicide in front of Rosa Amada at her family’s home. The exact nature of the events that night is still debated—some accounts suggest that he deliberately ended his life in a dramatic gesture of love, while others propose that the gun went off accidentally during a heated conversation. What is certain is that Silva’s death left an indelible mark on Ecuadorian literary history, cementing his image as a tragic, doomed poet whose intense emotions and unrequited love culminated in his early demise.

Beyond his romantic entanglements, Silva’s personal life was also marked by a deep sense of existential unease. He was known to suffer from bouts of depression, and there is evidence to suggest that he may have turned to drugs, particularly morphine, as a way to cope with his emotional pain. Some contemporaries noted his fragile mental state in the years leading up to his death, observing how his thoughts became increasingly consumed with death and despair. This preoccupation with mortality was not just a poetic affectation but a genuine reflection of his inner turmoil. His friends and family became concerned about his mental health, particularly as he began to speak more openly about suicide and the idea that life had lost its meaning for him.

Silva’s social isolation extended beyond his love life. As the only member of the Generación Decapitada from a lower socioeconomic background, he felt keenly the gap between himself and his peers, who hailed from elite families in Quito and Guayaquil. While his contemporaries Arturo Borja, Humberto Fierro, and Ernesto Noboa y Caamaño corresponded with and acknowledged Silva’s talent, he never felt fully integrated into their world. This sense of alienation was compounded by the racial prejudices of the time—his darker skin marked him as an outsider, even within the intellectual circles he longed to be a part of. Silva often expressed frustration with the societal constraints that limited his social mobility, and this feeling of being caught between worlds—intellectually gifted but socially marginalized—fueled much of the melancholy in his poetry.

In the final years of his life, Silva’s emotional fragility became increasingly apparent, as did his growing fixation on death. His poetry, already rich with references to mortality and decay, began to take on a more personal, confessional tone. Death was no longer an abstract concept for him; it was an impending reality. Whether consciously or unconsciously, Silva seemed to be preparing for the end, both in his writing and in his personal relationships. His final months were marked by a sense of inevitability, as if he believed that his destiny was already sealed.

In sum, Silva’s personal life was a complex web of unfulfilled desires, emotional pain, and existential isolation. His relationships, both familial and romantic, were tinged with tragedy, reflecting the larger themes of his literary work. The contradictions of his life—his desire for social acceptance clashing with the reality of his marginalization, his yearning for love thwarted by unreciprocated feelings, and his poetic genius overshadowed by his personal demons—all contributed to the making of one of Ecuador’s most iconic literary figures.

The Decapitated Generation

Medardo Ángel Silva was a central figure in the Generación Decapitada (Decapitated Generation), a group of four Ecuadorian poets—Silva, Arturo Borja, Humberto Fierro, and Ernesto Noboa y Caamaño—who became emblematic of modernismo in Ecuador. The group’s name was coined retrospectively by mid-20th-century journalists and historians, referencing both the early deaths of all four poets and the tragic, almost self-destructive themes in their works. None of them lived past their early 30s, with Silva and Borja both committing suicide. Their untimely deaths created an aura of fatalism and melancholy around the group, leading to the symbolic association with “decapitation.”

The Generación Decapitada was strongly influenced by the French symbolist poets, particularly Charles Baudelaire and Paul Verlaine, as well as the broader Spanish-American modernist movement led by Rubén Darío. Their works are suffused with a sense of existential despair, often focusing on themes of death, disillusionment, and the fleeting nature of beauty and love. These poets viewed life through a lens of inevitable decay, and their writing often explored the tension between idealized dreams and harsh realities. The emphasis on inner torment and the metaphysical preoccupation with death marked their poetry as distinctly modernist, characterized by an acute awareness of life’s impermanence and futility.

Although grouped together by their thematic concerns, the members of the Generación Decapitada were not an organized literary movement in the traditional sense. They did not collaborate formally or form a unified school of thought, unlike many other literary circles. Instead, they were linked more by shared existential preoccupations and similar literary influences than by personal or professional connections. Medardo Ángel Silva, for example, was from a lower social class than his contemporaries, which likely contributed to his feelings of isolation. Despite their lack of frequent personal interaction, Silva, Borja, Noboa y Caamaño, and Fierro recognized one another’s genius and occasionally dedicated poems to each other, a form of mutual literary recognition and respect.

The works of the Generación Decapitada brought modernismo to Ecuador at a time when the country was still largely conservative in its cultural expressions. Their poetry introduced a new level of introspection, emotional intensity, and stylistic innovation, which set them apart from their predecessors. While Darío’s influence is clearly present in their use of musicality, rich imagery, and symbolist techniques, they infused their works with a particularly Ecuadorean melancholy, reflective of both their personal struggles and the broader political and social upheavals in early 20th-century Ecuador.

Medardo Ángel Silva stands out among them as perhaps the most recognized today, partly due to the enduring popularity of his poem “El alma en los labios,” which was later adapted into a famous song. His obsession with death, reflected in much of his work, resonated deeply with his generation and later readers, cementing the Generación Decapitada as pioneers of Ecuadorian modernist literature. Their legacy is one of brilliant, though brief, artistic contribution, tied inextricably to the dark allure of early death and existential longing.

Death and Legacy

Medardo Ángel Silva’s life ended tragically and mysteriously on June 10, 1919, just two days after his 21st birthday. The circumstances of his death have been the subject of speculation and debate ever since. It is widely believed that Silva died by suicide, shooting himself in the presence of Rosa Amada Villegas, the young girl who had become both his muse and the object of his obsessive, unrequited love. However, some reports suggest that his death may have been accidental, with theories ranging from a tragic misfire to a symbolic, theatrical suicide staged to make an impression on Rosa. In any case, the fatal gunshot brought a dramatic and premature end to one of Ecuador’s most promising literary figures, transforming Silva into a near-mythic figure in Ecuadorian culture.

On the evening of June 10, Silva visited Rosa Amada at her family’s home, dressed in an elegant black suit with patent leather shoes, his usual appearance when attempting to present himself as more refined than his modest means allowed. After a brief conversation, during which he allegedly asked Rosa to sit closer to him, Silva shot himself in the head. According to one version of the story, he had only one bullet in the revolver, further fueling speculation that the event was premeditated. Rosa’s testimony many years later hinted at her discomfort and confusion in the moments leading up to the fatal shot, suggesting that she had not fully understood the depth of Silva’s despair. The fact that his death occurred in her presence and the deeply personal connection between his poetry and their relationship only added to the mystique surrounding his final moments.

Silva’s death, like that of his fellow poets in the Generación Decapitada (Decapitated Generation), cemented his reputation as a tragic figure—an artist consumed by inner torment and existential despair. The romanticism of his early death added a layer of myth to his legacy, casting him as the quintessential tormented poet whose life, marked by suffering and disillusionment, could only be fully realized through the ultimate act of self-destruction. In many ways, Silva’s death was a culmination of the dark themes that had pervaded his work—love, melancholy, and a yearning for release from life’s burdens.

Despite his brief life and relatively small body of work, Silva’s impact on Ecuadorian literature has been profound. His poetry, especially the haunting El alma en los labios (The Soul on the Lips), has left an indelible mark on Ecuadorian culture. The poem, written just days before his death and seemingly imbued with the knowledge of his impending fate, reflects the intensity of his emotions and the despair that consumed him. The lines of the poem express a willingness to end his life if the love he felt for Rosa Amada were ever to fade, a sentiment that tragically foreshadowed his final act. El alma en los labios became even more famous when it was set to music and performed as a pasillo by legendary Ecuadorian singer Julio Jaramillo, transforming Silva’s words into a cultural anthem of love and loss that resonates across generations. The song, which continues to be performed and remembered today, serves as a living testament to Silva’s influence on both literature and popular music in Ecuador.

Silva’s literary legacy, though shaped by his untimely death, has endured beyond his lifetime. While his career was cut short, the quality and depth of his work have continued to attract critical and scholarly attention. His writings have been compiled and republished multiple times, with the most comprehensive collection appearing in 2004 as part of the Obras Completas (Complete Works), an effort to preserve and celebrate his contributions to Ecuadorian literature. This edition brought together Silva’s poetry, prose, and essays, offering a fuller picture of his intellectual and emotional range.

Silva’s poetry stands out for its musicality, rich symbolism, and exploration of existential themes. Deeply influenced by the French symbolists and modernists, particularly Paul Verlaine and Charles Baudelaire, Silva’s works often reflect a tension between beauty and decay, love and death, and the fleeting nature of happiness. His exploration of these themes placed him at the forefront of Ecuador’s modernist movement and connected him to a broader Latin American literary tradition. Alongside his contemporaries in the Generación Decapitada, Silva helped to introduce modernismo to Ecuador, a literary movement that sought to innovate and break away from the classical forms of the past.

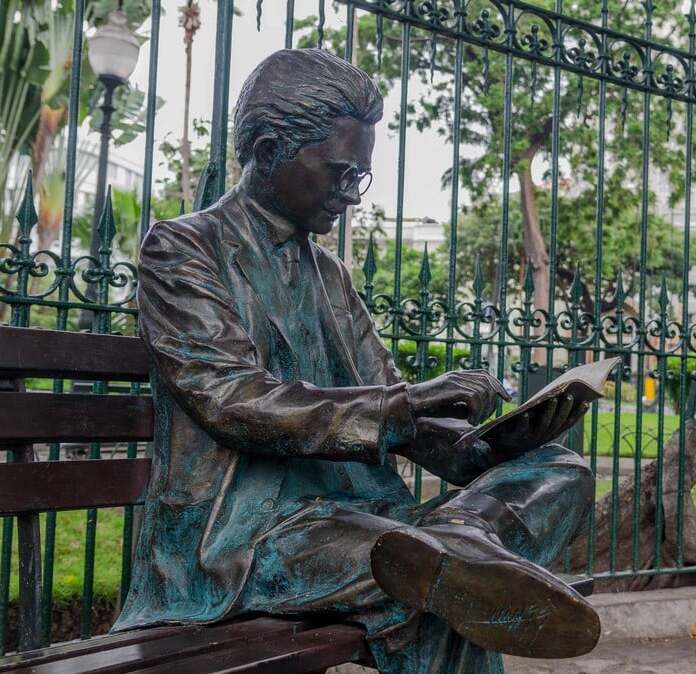

In Guayaquil, where Silva lived and died, his legacy is physically enshrined in public monuments that pay homage to his life and work. One of the most notable is the monument in San Agustín Park, located near the site of his death. The monument features a bronze statue of Silva seated on a bench, a book in his hands, inviting visitors to sit beside him—a poignant symbol of the poet’s enduring presence in the cultural memory of his city. The statue has become a place of pilgrimage for admirers of his work, as well as a tourist attraction, further cementing his status as a cultural icon in Ecuador.

In the decades since his death, Silva’s reputation has grown, both within Ecuador and across Latin America. He has come to symbolize not only the anguish of the Generación Decapitada, whose members all met tragic fates, but also the power of poetry to capture the deepest human emotions. His work remains a subject of study in Ecuadorian schools, and his influence is acknowledged by contemporary poets and scholars alike. Although his life was short, his poetry—filled with passion, despair, and a longing for transcendence—continues to speak to readers, ensuring that Medardo Ángel Silva’s legacy as one of Ecuador’s most important literary figures endures.

In 1926, Gonzalo Zaldumbide compiled Silva’s Poesías escogidas (Selected Poems), ensuring the preservation of his literary contributions. His life and work were later memorialized in the 2015 film Medardo, which explored his passionate and tragic life.

Timeline of Key Events and Posthumous Developments

1898: Birth

- June 8, 1898: Medardo Ángel Silva was born in Guayaquil, Ecuador, into a family with a rich musical background. His father, Enrique Silva Valdés, was a mulatto pianist and piano tuner, and his mother, Mariana Rodas Moreira, was a poet.

1902: Death of His Father

- 1902: Silva’s father, Enrique, died of tuberculosis when Medardo was only three years old. This tragedy left his mother, Mariana, to raise him alone in an economically difficult situation.

Early 1900s: Childhood and Education

- 1904: Silva began attending the Filantrópica School, a free institution in Guayaquil that provided education for working-class children. Silva excelled academically despite his family’s financial struggles.

- During his childhood, he developed a deep interest in literature and music, often reciting poems by José Joaquín de Olmedo and showing early signs of poetic talent. His intellectual and artistic inclinations were nurtured by his mother, who recognized his potential.

1910: Entered Vicente Rocafuerte High School

- 1910: At the age of 11, Silva was accepted into the prestigious Vicente Rocafuerte High School in Guayaquil. His education there exposed him to broader ideas in literature, philosophy, and the sciences, and he developed a keen interest in European literature, particularly the works of French and Spanish poets.

1912-1914: Early Poetic Attempts

- 1912-1913: Silva started composing poems and submitting them to local newspapers and literary magazines. His early works, heavily influenced by Romanticism and Modernismo, were often rejected due to his youth and lack of connections.

- 1914: His early attempts were published in the magazine Juan Montalvo. These publications marked the beginning of his rise in Ecuadorian literary circles. At this time, he was already influenced by Rubén Darío’s modernismo and French symbolism.

1915: First Recognitions

- 1915: Silva adopted the pseudonyms “Jean D’Agreve” and “Oscar René” for some of his works, reflecting his literary influences, particularly from French authors. His poems began to receive attention in national magazines, leading to his growing reputation.

1917: Shift to Journalism and Poetry Recognition

- 1917: At the age of 19, Silva gained a position as a teacher at a local school to support his family financially, but he never abandoned his literary ambitions. His works continued to be published in various Ecuadorian magazines, and he also began contributing essays, short stories, and poetry to international publications like Nosotros in Buenos Aires and Cervantes in Madrid.

- 1917: Silva also started working as a journalist and literary editor for El Telégrafo, one of Ecuador’s most prestigious newspapers. He managed the “Los jueves literarios” section and published his columns under the pseudonym “Jean D’Agreve,” which allowed him to share his reflections on literature and society.

1918: First Poetry Book

- 1918: Silva self-published his first and only book of poetry, El árbol del bien y del mal (The Tree of Good and Evil), which encapsulated his melancholic, modernist style. The book contained sections such as “Las Voces Inefables” (The Ineffable Voices), “Estancias” (Stanzas), and “Libro de Amor” (Book of Love), exploring themes of love, fantasy, and death.

- This publication solidified Silva’s status as one of the most promising young poets in Ecuador.

1918: Personal Life Developments

- 1918: Silva had a daughter, María Mercedes Cleofé Silva Carrión, with Ángela Carrión Vallejo, a woman who lived with his family. However, their relationship was kept relatively private. Silva’s personal life was marked by emotional turbulence, and he struggled with feelings of isolation due to his modest background and darker complexion, particularly compared to his peers in the Generación Decapitada (Decapitated Generation).

1919: Novella and Continued Rise in Journalism

- 1919: Silva published his novella María Jesús in serialized form in El Telégrafo. The novella, a rural love story, showcased his skills as a prose writer and revealed his yearning for idealized love. It was his only major prose work and gained attention for its lyrical style.

- 1919: Silva continued working at El Telégrafo as a literary editor, where he further established his influence in Ecuadorian journalism. His columns and editorial work promoted new literary voices and modernist aesthetics.

1919: Relationship with Rosa Amada Villegas

- 1919: Silva developed a deep romantic infatuation with Rosa Amada Villegas, a 14-year-old girl who became the inspiration for his famous poem El alma en los labios (The Soul on the Lips). This relationship, though brief and largely unreciprocated by Rosa, became central to the legend surrounding Silva’s life and death.

June 8, 1919: 21st Birthday

- June 8, 1919: Silva celebrated his 21st birthday. This milestone came just two days before his tragic death, a period marked by deepening emotional turmoil and feelings of despair, particularly over his unrequited love for Rosa Amada.

June 10, 1919: Tragic Death

- June 10, 1919: Medardo Ángel Silva died from a gunshot wound in the presence of Rosa Amada Villegas. While widely believed to be a suicide, the circumstances of his death remain unclear, with some reports suggesting it may have been accidental. His death occurred just two days after his 21st birthday and solidified his reputation as the quintessential “doomed poet” of Ecuador. Silva’s poem El alma en los labios, written shortly before his death, became a haunting reflection of his inner turmoil.

1920s: Posthumous Recognition

- 1926: Gonzalo Zaldumbide compiled and published Poesías escogidas (Selected Poems), ensuring Silva’s poetry continued to be appreciated by future generations.

- Over the years, Silva’s tragic story and his deep, melancholic poetry cemented his place in Ecuadorian literary history as a member of the Generación Decapitada.

Mid-20th Century: Legacy

- Mid-20th Century: Silva was posthumously grouped with Arturo Borja, Humberto Fierro, and Ernesto Noboa y Caamaño as part of the Generación Decapitada (Decapitated Generation), named by journalists and historians due to the early deaths and tragic themes in their work.

2004: Publication of Obras Completas

- 2004: The Project of Editorial Rescue at the Biblioteca Municipal of Guayaquil published Silva’s Obras Completas (Complete Works), bringing together his poetry, prose, and journalistic writings. This edition provided a comprehensive collection of Silva’s literary output.

2015: Film Depiction

- 2015: Silva’s life and work were further immortalized with the release of the film Medardo, which explored his passionate, tragic life and his role as one of Ecuador’s most significant poets.

Present Day: Ongoing Legacy

- Present Day: Medardo Ángel Silva continues to be one of Ecuador’s most celebrated literary figures. His work is taught in schools, and his poetry, particularly El alma en los labios, remains a cultural touchstone. His contributions to modernism in Ecuadorian literature and his tragic personal story have ensured his place in the country’s literary canon.

Pictures

Left: Rosa Amada Villegas’ house where Silva died. It was demolished in 1969. Photo taken from Abel Romeo Castillo’s book. Right: There is currently a hostel in operation. Courtesy of Esmeralda Muñoz.

A short documentary

Poem

| El alma en los labios | My Soul on My Lips |

|---|---|

| (Spanish text) by Medardo Ángel Silva | (English translation by Richard Gabela April 20, 2024) |

| Cuando de nuestro amor, la llama apasionada, dentro tu pecho amante contemples extinguida, que solo por ti la vida me es amada, el día en que me faltes me arrancaré la vida. Porque mi pensamiento, lleno de este cariño, que en una hora feliz me hiciera esclavo tuyo, lejos de tus pupilas es triste como un niño, que se duerme soñando en tu acento de arrullo. Para envolverte en besos, quisiera ser el viento, y quisiera ser todo lo que tu mano toca. Ser tu sonrisa, ser hasta tu mismo aliento, para poder estar mas cerca de tu boca. Vivo de tus palabras y eternamente espero llamarte mía, como quien espera un tesoro; lejos de ti comprendo, lo mucho que te quiero, y besando tus cartas, ingenuamente te lloro, Perdona si no tengo palabras con que pueda decirte la inefable pasión que me devora. Para expresar mi amor solamente me queda rasgarme el pecho, amada, y en tus manos de seda dejar mi palpitante, corazón que te adora. | When the passionate flame of our love, you behold extinguished within your loving heart— as only for you is life beloved to me— the day you are gone, I will tear my life away. Because my mind, filled with this tender affection that in one blissful hour made me your slave, far from your eyes grows as sad as a child who falls asleep dreaming of your lullaby voice. To shower you with kisses, I yearn to be the wind, and long to become everything your hand touches. To be your smile, to be even your very breath, just to be nearer your lips. I live on your words and forever await to call you mine, like one who seeks a treasure. Away from you, I truly understand how much I love you, and kissing your letters, I ingenuously weep for you. Forgive me if I lack the words to convey the ineffable passion that consumes me. To show my love, all I can do is to tear open my chest, beloved, and into your silken hands lay my throbbing heart that adores you. |

Works

- El árbol del bien y del mal (1918)

- María Jesús (1919)

- La máscara irónica (essays)

- Trompetas de oro

- El alma en los labios

- Obras Completas (2004) (Complete Works)

References

- Wikipedia, “Medardo Ángel Silva.” Retrieved on September 30, 2024.

- Rodolfo Pérez Pimentel, “Medardo Ángel Silva.” Retrieved on September 30, 2024.

- Ministerio de Cultura y Patrimonio, “Medardo Ángel Silva.” Retrieved on September 30, 2024.

- Enciclopedia de Ecuador, “Medardo Ángel Silva.” Retrieved on September 30, 2024.

- EcuRed, “Medardo Ángel Silva.” Retrieved on September 30, 2024.