Tzantzismo was a cultural movement from Ecuador’s 1960s. It was founded in Quito by Marco Muñoz and Ulises Estrella, while the rest of the members came together throughout the decade. They were influenced by other Ecuadorian intellectuals such as Jorge Enrique Adoum, César Dávila Andrade and Agustín Cueva. Tzantzismo was expressed primarily in poetry, and to a lesser extent in fiction and theater. This literary revolutionary movement emerged in response to an alleged degradation and gentrification of Ecuadorian literature. An important book on the movement’s history was written by author Susana Freire García.

Early Beginnings and Founding Members

Tzantzismo was a cultural and literary movement that emerged in Ecuador during the 1960s. It was founded in Quito in 1962 by Marco Muñoz and Ulises Estrella, with other members joining throughout the decade. The movement was a reaction against what its members perceived as a degradation and gentrification of Ecuadorian literature. They sought to challenge the established norms of society and literature, drawing inspiration from other Ecuadorian intellectuals such as Jorge Enrique Adoum, César Dávila Andrade, and Agustín Cueva.

Influences and Name Significance

The movement’s name, “Tzantzismo,” is derived from the Shuar word “tzantza,” which refers to the practice of shrinking an enemy’s head as a symbol of victory and power. This metaphor was apt for the group’s mission to “shrink” the heads of traditionalism and societal norms, thus opening up the minds of Ecuadorians to new forms of cultural and literary expression. The Tzántzicos, as the movement’s members were called, adopted a revolutionary image, often wearing long beards and hair in homage to Fidel Castro, and choosing jeans as a symbol of their defiance against mainstream societal expectations.

Activities and Manifesto

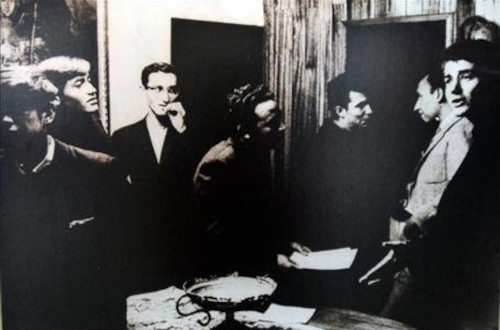

Initially, the Tzántzicos gathered at the home of painter Eliza Aliz (Elizabeth Rumazo) and her Cuban husband René Aliz. Later, their meetings took place at the Café Águila de Oro, which they renamed “77 Café.” Here, they engaged in intense discussions on poetry, politics, and culture. Tzantzismo officially began with the publication of the poetry collection “Clamor,” co-authored by Ulises Estrella and Argentine poet Leandro Katz in 1962. On August 27 of the same year, the first Tzántzico Manifesto was signed by Marco Muñoz, Alfonso Murriagui, Simón Corral, Teodoro Murillo, Euler Granda, and Ulises Estrella, marking the formal inception of the movement.

Literary Contributions and Ideology

Tzantzismo was primarily a poetic movement but also extended its influence into fiction and theater. It sought to break away from conventional literary forms, promoting a more direct and accessible style of writing. Raúl Arias, one of the movement’s most prominent figures, exemplified this approach in his poetry collection “Poesia en bicicleta,” which is considered one of the best representations of Tzantzismo. The Tzántzicos were also known for their public recitals and performances, which were marked by their provocative and challenging nature. They often took to public spaces such as plazas, schools, and unions to share their work, aiming to reach a broader audience and make literature more accessible.

Dissolution and Legacy

Despite its significant impact on Ecuadorian literature and culture, Tzantzismo was relatively short-lived, dissolving in 1969 due to ideological differences among its founders. However, its influence persisted, and it is credited with modernizing Ecuadorian poetry and redefining the role of the intellectual in society. The movement challenged the status quo and questioned the cultural elitism of the time, leaving a lasting mark on the Ecuadorian literary landscape.

Notable Members

In addition to its founders Marco Muñoz and Ulises Estrella, the Tzántzicos included a diverse group of intellectuals and artists. Some of the notable members were:

- Abdón Ubidia (Quito, 1944)

- Agustín Cueva (Ibarra, 1937)

- Alejandro Moreano (Quito, 1945)

- Alfonso Murriágui (Quito, 1929)

- Álvaro Juan Félix

- Antonio Ordóñez (Quito, 1943)

- Bolívar Echeverría (Riobamba, 1941)

- Euler Granda (Riobamba, 1935)

- Fernando Tinajero (Quito, 1980)

- Francisco Proaño Arandi (Cuenca, 1944)

- Humberto Vinueza (Guayaquil, 1942)

- Iván Carvajal (San Gabriel, 1948)

- Iván egüez (Quito, 1944)

- José Ron

- José Corral

- Leandro Katz (Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1938)

- Luis Corral

- Marco Muñoz

- Marco Velasco

- Rafael Larrea

- Raúl Arias (Quito, 1943)

- Simón Corral (1946)

- Sonia Romo Verdesoto, the movement’s only female member.

- Teodoro Murillo (1944)

- Ulises Estrella (1939)

Though some like Agustín Cueva and Fernando Tinajero were not formal members, they were closely associated with the movement, sharing similar ideological perspectives.

Publications and Continuing Influence

The Tzántzicos were prolific in their publications, often using literary magazines as platforms for their work and ideas. One of the most significant publications of the movement was the magazine “Pucuna,” named after the blowgun used by the Shuar to shoot poisoned darts, symbolizing the group’s aim to ‘attack’ cultural stagnation. Other notable magazines included “La Bufanda del Sol” and “Indoamérica.” The movement’s history and contributions have been chronicled in books such as Tzantzismo: Tierno e insolente by Susana Freire García and Los años de la fiebre, compiled by Ulises Estrella.

Conclusion

Tzantzismo, while a brief chapter in Ecuadorian cultural history, played a crucial role in challenging and transforming the country’s literary and cultural scene. By rejecting traditionalism and advocating for a more radical and accessible approach to literature and art, the Tzántzicos paved the way for future generations of writers and intellectuals in Ecuador. Their legacy endures in the continued recognition of their contributions to Ecuadorian and Latin American literature.

Documentary about the Tzántzicos

Alfonso Murriagui speaks about the Tzántzicos

In Fiction:

The Tzántzico cultural movement has a prominent role in the novel La disfiguración Silva, published in 2015 by the Ecuadorian writer Mónica Ojeda and winner of the ALBA Narrative Award. In the book, the protagonists obtain an enigmatic script for a film supposedly written by Gianella Silva, a screenwriter and the only woman member of the Tzántzico cultural movement, who history had forgotten.