Benjamín Carrión Mora (Loja, April 20, 1897 – Quito, March 8, 1979) was one of the great Latin American intellectuals of the 20th century. He was a lawyer, writer, novelist, poet, essayist, biographer, literary critic, legislator, diplomat, educator and cultural promoter. His most notable literary work is Atahualpa (1934), a biography written in story form about the last Inca emperor, which has been translated into English and French. In 1944 Carrión founded the House of Ecuadorian Culture, which preserves and promotes many aspects of Ecuador’s culture, including music, dance, art, literature, theater and film. Considered Carrión’s greatest achievement and legacy, this organization maintains several museums, libraries and performance venues throughout Ecuador, as well as a printing press which has been instrumental in publishing many noteworthy Ecuadorian authors.

Early Life and Education

Benjamín Carrión was born on April 20, 1897, in Loja, a city in southern Ecuador, into an intellectual and literary family. His father, Manuel Alejandro Carrión Riofrío, was a professor of literature and a poet, whose influence left a deep impression on the young Carrión. However, his father’s death in 1903, when Carrión was just six years old, meant that his early education was primarily shaped by his mother, Filomena Mora Bermeo. Filomena was well-educated and a voracious reader, particularly of French literature, and she passed on her love of reading and intellectual curiosity to her son.

Despite the early loss of his father, Carrión’s childhood was intellectually rich. He did not attend formal primary school; instead, his mother tutored him at home, teaching him the basics of reading, writing, and some French. Her influence nurtured his lifelong passion for literature. Carrión later attended Colegio Bernardo Valdivieso in Loja for his secondary education. There, his literary interests flourished under the mentorship of teachers like Adolfo Valarezo, who encouraged his exploration of culture and literature. His brother Héctor Manuel also played a key role in introducing him to modernist poets like Baudelaire and Rimbaud, which deepened his literary sensibilities.

Carrión excelled in his studies, particularly in mathematics, but his true passion was always literature and culture. His involvement in local literary and intellectual circles during his teenage years allowed him to begin contributing to newspapers and magazines, marking the start of his lifelong engagement with writing and public discourse.

In 1916, after completing his secondary education, Carrión moved to Quito to pursue a law degree at the Central University of Ecuador. His time in Quito exposed him to the city’s vibrant intellectual life, and he quickly became involved in student activism and literary societies. These activities connected him with important figures in Ecuadorian intellectual life, such as Ernesto Noboa Caamaño and Humberto Fierro, with whom he shared a vision of modernizing Ecuadorian society through literature and culture.

While at university, Carrión continued to write prolifically, contributing to various periodicals. His involvement in the Federation of University Students (Federación de Estudiantes Universitarios, FEU) reflected his growing interest in politics, as he pushed for reforms in Ecuador’s educational system and supported the broader university reform movement that was sweeping through Latin America at the time.

Although Carrión graduated with a degree in law, his career as a lawyer was short-lived. His passion for writing and cultural advocacy soon led him to pursue a broader intellectual and diplomatic career, through which he would make his most significant contributions.

Literary Career

Benjamín Carrión Mora’s literary career spanned over five decades, during which he emerged as one of Ecuador’s most influential intellectuals. His writing combined sharp political commentary with cultural advocacy, making him not just a literary figure but a powerful voice for Ecuadorian and Latin American identity. Carrión’s works encompass a range of genres, including essays, novels, biographies, critiques, and anthologies. His career was deeply intertwined with his political ideals, which often reflected his socialist leanings and his vision of a unified Latin American cultural identity.

Early Literary Influences and Beginnings (1910s–1920s)

Carrión’s literary inclinations were nurtured early on through exposure to French literature, particularly the works of poets such as Baudelaire and Rimbaud, introduced to him by his brother Héctor Manuel. His time in Loja and later in Quito allowed him to become deeply involved in Ecuador’s intellectual circles, where he collaborated with leading writers and thinkers.

In 1918, while still a student at the Central University of Ecuador, he achieved early recognition by winning several literary prizes at the Juegos Florales, a literary competition. He won the Jazmín de Plata for his poem Romance antiguo and the Flor Natural for Confesión lírica. In prose, he was awarded first prize for Mariana. These accolades solidified his standing as a rising literary talent in Ecuador and marked the beginning of his public literary career.

During the 1920s, Carrión began writing for newspapers and journals, contributing essays, critiques, and short stories. His early works reflected his interest in Latin American identity, culture, and politics, as well as his growing dissatisfaction with Ecuador’s political elite. His writings often focused on social justice and the need for a more progressive cultural narrative, a theme that would become central throughout his career.

Los Creadores de la Nueva América (1928)

Carrión’s first major work, Los Creadores de la Nueva América (The Creators of the New America), was published in 1928 in Paris with a foreword by Nobel laureate Gabriela Mistral. This book was a collection of essays on four influential Latin American intellectuals—José Vasconcelos (Mexico), Manuel Ugarte (Argentina), Francisco García Calderón (Peru), and Alcides Arguedas (Bolivia). Through these essays, Carrión examined the potential for a “New America” that could challenge European cultural dominance by asserting a unique Latin American identity grounded in its own history, people, and cultures.

The work was groundbreaking in its scope and ambition. It marked one of the first attempts by a Latin American intellectual to systematically analyze the contributions of his continent’s thinkers to the broader cultural and intellectual landscape. Carrión emphasized the importance of culture in the political and social formation of Latin America, laying the groundwork for his lifelong advocacy of cultural nationalism.

El Desencanto de Miguel García (1929)

Carrión’s 1929 novel El Desencanto de Miguel García (The Disillusionment of Miguel García) is a scathing critique of Ecuadorian politics and social customs. The novel’s protagonist, Miguel García, navigates the corrupt and stagnant political systems of his country, reflecting Carrión’s growing frustration with the political elites. Although the novel did not garner immediate widespread attention, it demonstrated Carrión’s ability to merge fiction with social and political critique, a theme that would recur in his later works.

Mapa de América (1930)

In Mapa de América (1930), Carrión provided a broader analysis of Latin American literary and intellectual movements. With a foreword by the Spanish writer Ramón Gómez de la Serna, the book highlighted some of the most important contemporary authors, such as Teresa de la Parra, Pablo Palacio, Jaime Torres Bodet, and José Carlos Mariátegui. Carrión’s essay on Mariátegui, a Marxist Peruvian intellectual, was particularly significant. In it, Carrión explored the concept of rejecting the Eurocentric view of America and instead advocated for an authentic cultural synthesis that would blend European and indigenous influences.

Mapa de América was one of Carrión’s most important critical works. It served as both a literary critique and a manifesto for Latin American cultural independence. Through it, Carrión sought to elevate Latin American literature on the world stage, arguing that it could stand alongside the great literary traditions of Europe and North America.

Atahuallpa (1934)

Carrión’s most celebrated work, Atahuallpa (1934), was a historical novel about the last Inca emperor, Atahualpa, and his tragic clash with Spanish colonizers. Though categorized as a biography, the work blended historical fact with imaginative fiction, and its narrative style resembled that of a novel. In the book, Carrión explored the themes of conquest, cultural destruction, and resistance, positioning Atahualpa as both a tragic hero and a symbol of Ecuador’s indigenous heritage.

Written during a time of heightened nationalist sentiment following Ecuador’s territorial conflicts with Peru, Atahuallpa served as a reflection on Ecuador’s history and identity. Carrión’s portrayal of Atahualpa as a noble, albeit flawed, leader provided a mythic origin story for modern Ecuador, which Carrión linked to the country’s fight for sovereignty. The novel was widely praised for its rich historical detail and its symbolic representation of Ecuador’s national consciousness.

The book’s success transcended national boundaries; it was translated into English and French, making Carrión one of Ecuador’s most internationally recognized authors. Atahuallpa is often considered one of the earliest and most important works of modern Ecuadorian literature, helping to define the country’s literary canon.

Cartas al Ecuador (1943)

In 1943, Carrión published Cartas al Ecuador (Letters to Ecuador), a collection of essays that addressed the political and cultural challenges facing his country. The essays were written in the aftermath of Ecuador’s defeat in the 1941 war with Peru and the signing of the Rio de Janeiro Protocol, in which Ecuador ceded disputed territories. Carrión saw this event as a national humiliation, and his essays were a call to cultural action. He believed that the way to reclaim Ecuador’s dignity was through cultural development, not military might.

In Cartas al Ecuador, Carrión introduced his concept of the “small great nation,” in which he argued that Ecuador, despite its geographical and political limitations, could become a cultural power through its intellectual and artistic achievements. These essays solidified Carrión’s reputation as both a literary critic and a cultural leader, and the book became a foundational text in Ecuador’s intellectual discourse.

San Miguel de Unamuno (1954) and Santa Gabriela Mistral (1956)

In the 1950s, Carrión published two important biographical essays: San Miguel de Unamuno (1954), on the Spanish philosopher Miguel de Unamuno, and Santa Gabriela Mistral (1956), on the Chilean poet Gabriela Mistral. Both works were part of Carrión’s broader project to build a “secular sainthood” of Latin American and Spanish intellectuals who represented the highest ideals of cultural and philosophical thought. In San Miguel de Unamuno, Carrión analyzed the philosopher’s ideas on faith, doubt, and the role of intellectuals in society, while Santa Gabriela Mistral delved into the poet’s mystical and maternal themes, underscoring her role as a symbol of Latin American identity.

These works highlighted Carrión’s deep admiration for both authors and his belief that they had transcended national boundaries to become universal figures. His ability to connect their works to broader Latin American cultural themes reinforced his status as a leading literary critic.

García Moreno, el Santo del Patíbulo (1958)

One of Carrión’s most controversial works was García Moreno, el Santo del Patíbulo (García Moreno, the Saint of the Scaffold), a satirical biography of Ecuador’s 19th-century conservative president Gabriel García Moreno. Written during a time when García Moreno’s canonization process was being considered by the Catholic Church, Carrión sought to counter the narrative of García Moreno as a saintly figure. Instead, he depicted him as an authoritarian ruler who imposed his conservative, religious agenda on Ecuador.

The book was deeply polarizing and sparked significant debate in Ecuador. Carrión’s biting prose and extensive use of historical documentation made the book both a literary and historical achievement. It has since been compared to other Latin American “dictator novels” such as El Señor Presidente by Miguel Ángel Asturias and Yo, el Supremo by Augusto Roa Bastos.

Late Career and Final Works

Carrión continued to write prolifically throughout his life. In Raíz y Camino de Nuestra Cultura (1970), he offered a comprehensive analysis of Ecuadorian culture, focusing on its indigenous, European, and African roots. This work reflected his belief that Ecuador’s national identity was inherently multicultural, shaped by the complex interplay of different cultural traditions.

His last major work, América Dada al Diablo (1981), was published posthumously. In it, Carrión expressed his disappointment with the direction of Latin American politics and culture, lamenting the region’s continued struggles with underdevelopment and inequality. Despite this pessimism, he remained a staunch advocate for the transformative power of culture.

Political and Diplomatic Life

Benjamín Carrión’s political and diplomatic career was as influential as his literary endeavors, and the two often overlapped. His work in diplomacy, government service, and party politics was rooted in his desire to reshape Ecuadorian society through cultural and political means. A committed socialist with a passion for education and national identity, Carrión saw culture as a tool for political and social transformation. His time as a diplomat, minister, and political leader allowed him to spread these ideas both within Ecuador and internationally.

Early Political Involvement and Socialist Party Leadership

Carrión’s political life began during his university years in Quito, where he became involved in student activism. In 1919, while studying law at the Central University of Ecuador, he co-founded the Federation of University Students (FEU), which played a pivotal role in pushing for progressive reforms in Ecuador’s educational system. This movement aligned with the broader university reform movement inspired by the 1918 Cordoba reforms in Argentina, which sought greater autonomy and democratic governance within Latin American universities.

By the mid-1920s, Carrión had aligned himself with the emerging socialist movement in Ecuador. In 1926, he was a founding member of the Ecuadorian Socialist Party (Partido Socialista Ecuatoriano), a significant political force advocating for workers’ rights, land reform, and a more equitable distribution of wealth. Carrión quickly rose through the party’s ranks, becoming Secretary General of the Socialist Party in 1932. He played a key role in shaping the party’s intellectual direction, blending Marxist and nationalist ideas with his own vision of cultural renewal.

Diplomatic Posts in Europe and Latin America

In 1925, Carrión began his diplomatic career when President Gonzalo Córdova appointed him as Ecuador’s consul in Le Havre, France. This position was his first major role outside Ecuador and provided him with the opportunity to immerse himself in European intellectual circles. During his time in France, Carrión deepened his relationships with prominent Latin American and European intellectuals, including Gabriela Mistral, José Vasconcelos, and Miguel de Unamuno. He also studied at the prestigious École des Hautes Études in Paris, where he continued his intellectual development and began writing more extensively on cultural and political issues.

Carrión’s time in France (1925–1929) was instrumental in shaping his views on the role of culture in politics. He came to see Latin American culture as a potential force for unity and resistance against the cultural hegemony of Europe and the United States. This perspective would later influence his diplomatic work, particularly in his efforts to promote Ecuadorian and Latin American culture on the world stage.

In 1933, after returning to Ecuador, Carrión was appointed Ecuador’s Ambassador to Mexico, where he served until 1934. His tenure in Mexico was particularly significant, as the country was experiencing a cultural renaissance under the leadership of President Lázaro Cárdenas. The influence of Mexico’s cultural policies, especially the state’s investment in the arts and education, reinforced Carrión’s belief in the power of cultural institutions as agents of national development. During his time as ambassador, Carrión maintained close relations with leading Mexican intellectuals and artists, including Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros, as well as continuing his friendship with Vasconcelos.

Minister of Public Education and Political Challenges

Carrión’s diplomatic career was punctuated by his involvement in domestic politics. In 1933, he briefly served as Ecuador’s Minister of Public Education during the presidency of Juan de Dios Martínez Mera. Carrión’s appointment to this position reflected his growing stature in Ecuadorian political life, and he used the office to advocate for progressive reforms in the educational system, aiming to make education more accessible and more aligned with Ecuador’s cultural identity. His tenure, however, was short-lived, as political instability forced Martínez Mera out of office, bringing Carrión’s ministerial role to an abrupt end.

Despite this setback, Carrión remained a significant figure in Ecuadorian politics throughout the 1930s. After Martínez Mera’s ousting, Carrión continued his work within the Socialist Party and served as Ecuador’s ambassador to Colombia from 1937 to 1939. His time in Colombia coincided with a period of political volatility, as Colombia was navigating its own conflicts between conservative and liberal forces. Carrión’s diplomatic efforts were focused on maintaining stable relations between Ecuador and Colombia, particularly after Ecuador’s brief military conflict with Peru in 1941, which resulted in the loss of significant Amazonian territory under the Rio de Janeiro Protocol.

The War with Peru and Its Political Aftermath

The 1941 border conflict with Peru was a turning point in Ecuadorian politics and for Carrión personally. The war, which ended in a decisive defeat for Ecuador, led to the signing of the Rio de Janeiro Protocol in 1942, in which Ecuador agreed to cede large portions of the Amazon region to Peru. The territorial losses deeply affected Ecuadorian national consciousness, and Carrión, like many of his compatriots, saw the conflict as a national humiliation.

Carrión’s response to this defeat was not militaristic but cultural. In his 1943 essays Cartas al Ecuador, Carrión argued that Ecuador could not reclaim its dignity through war but through a renewed focus on culture, education, and national identity. He called for the creation of institutions that could foster a sense of national pride and cultural achievement, leading to his founding of the Casa de la Cultura Ecuatoriana the following year.

Founding of the Casa de la Cultura Ecuatoriana (1944)

In 1944, following the ousting of President Carlos Arroyo del Río and the return of José María Velasco Ibarra to power, Carrión founded the Casa de la Cultura Ecuatoriana, his most significant political and cultural achievement. The Casa de la Cultura was established with the mission of promoting Ecuadorian arts, literature, and intellectual life, serving as a hub for the country’s cultural development.

Carrión became the first president of the Casa de la Cultura, a position he held from 1944 to 1948 and again from 1961 to 1967. His leadership helped establish the institution as a major cultural force in Ecuador, providing support for writers, artists, musicians, and intellectuals. The Casa housed museums, libraries, and performance venues, and published works by Ecuadorian authors, many of whom might otherwise have struggled to find a platform. Carrión’s vision was for Ecuador to become a “small great nation” by emphasizing its cultural achievements, and he worked tirelessly to build the Casa de la Cultura into a symbol of national pride and intellectual vitality.

Carrión’s cultural diplomacy extended beyond Ecuador’s borders. He invited international artists and intellectuals to visit and collaborate with Ecuadorian institutions, thereby integrating Ecuador into the broader Latin American and global cultural community. He also played a key role in the creation of the Letras del Ecuador literary magazine, which provided a platform for Ecuadorian writers to reach a broader audience.

Return to Diplomacy: Ambassador to Chile (1948) and Mexico (1968)

Carrión’s diplomatic career continued with his appointment as Ecuador’s ambassador to Chile in 1948. His time in Chile was brief, but he used his position to strengthen cultural and intellectual ties between the two countries. He returned to Ecuador shortly after to resume his leadership of the Casa de la Cultura and continue his cultural work.

In 1968, Carrión was once again appointed Ecuador’s Ambassador to Mexico. His second tenure in Mexico was during a period of intense cultural exchange between the two countries. Mexico had long been a cultural powerhouse in Latin America, and Carrión used his diplomatic post to promote Ecuadorian culture abroad. During this time, he was awarded the Benito Juárez Prize, one of the highest honors given by the Mexican government, in recognition of his contributions to Latin American culture.

Candidacy for Vice President (1960) and Political Setbacks

In 1960, Carrión entered national politics more directly by running for Vice President of Ecuador alongside Antonio Parra Velasco, a prominent lawyer and academic. Their campaign slogan, “Parra, Carrión, por la revolución,” reflected their shared vision for a progressive, left-leaning administration that would prioritize education, culture, and social justice.

The election, however, did not result in victory. Despite the support of student movements and intellectuals, Carrión and Parra were defeated by conservative forces. This loss marked the end of Carrión’s direct political ambitions, but it did not diminish his influence in Ecuadorian political and cultural life.

Final Years and Contributions to Democratic Governance

In the last years of his life, Carrión focused on consolidating the cultural institutions he had helped build and promoting democratic governance in Ecuador. In 1978, he was appointed President of the Supreme Electoral Tribunal of Ecuador, where he oversaw the country’s transition to democratic elections following years of military rule. This position reflected Carrión’s deep commitment to democratic principles and his belief in the role of culture in supporting political stability.

Legacy in Politics and Diplomacy

Benjamín Carrión’s political and diplomatic career was marked by his unwavering belief in the transformative power of culture. He saw culture as a means to elevate Ecuador on the global stage and to heal the divisions within his country. His work in diplomacy helped establish Ecuador’s cultural presence internationally, while his leadership of the Casa de la Cultura Ecuatoriana ensured that generations of Ecuadorian artists and intellectuals would have a platform to share their work.

Cultural Promotion and the Casa de la Cultura Ecuatoriana

The founding of the Casa de la Cultura Ecuatoriana (CCE) in 1944 was the crowning achievement of Benjamín Carrión’s career and his most lasting contribution to Ecuadorian society. The CCE was not just an institution; it was the manifestation of Carrión’s vision of culture as a transformative force for national identity and progress. He believed that in the aftermath of Ecuador’s defeat in the 1941 border war with Peru, Ecuador’s strength would come not from military power but from the promotion of its cultural and intellectual heritage. Through the CCE, Carrión sought to redefine Ecuador’s national consciousness by focusing on the arts, literature, and education, ensuring that culture became the bedrock of Ecuadorian identity.

Founding of the Casa de la Cultura Ecuatoriana (1944)

Carrión’s decision to establish the CCE came at a crucial moment in Ecuador’s history. The loss of territory to Peru in 1941 and the signing of the Rio de Janeiro Protocol in 1942 had left the country demoralized and struggling with a sense of national inferiority. Carrión believed that a cultural revival was necessary to restore Ecuador’s dignity and to project a positive national image both at home and abroad. His vision was to create an institution that could serve as a beacon for Ecuadorian arts, letters, and intellectual life—a place where the country’s best and brightest could come together to shape Ecuador’s future through culture.

The Casa de la Cultura Ecuatoriana was formally established on August 9, 1944, in Quito, with Carrión as its first president. He quickly set about building the institution into a national cultural hub. Carrión conceived of the CCE as a dynamic institution that would promote and protect Ecuadorian culture by offering artists, writers, and intellectuals a platform for creative expression. The mission of the CCE was to “stimulate, direct, and coordinate the development of an authentic national culture,” one that would reflect Ecuador’s unique blend of indigenous, European, and African influences.

Structure and National Reach

One of the CCE’s greatest innovations was its decentralized structure. Carrión was determined that the institution should not only serve the capital, Quito, but also reach into every province of Ecuador. To this end, he established a network of regional branches (núcleos) across the country. These branches were tasked with fostering local artistic talent, preserving regional cultural traditions, and ensuring that the benefits of cultural promotion were not limited to urban elites. Over the years, these núcleos spread to cities such as Cuenca, Guayaquil, and Loja, turning the CCE into a truly national institution.

Each núcleo maintained its own cultural agenda, organizing exhibitions, performances, and conferences, while also contributing to the CCE’s broader mission. This decentralized approach allowed the CCE to become a grassroots organization, deeply embedded in the cultural life of Ecuador’s diverse regions. It promoted cultural unity while also celebrating the country’s regional diversity.

Museums, Libraries, and Performance Venues

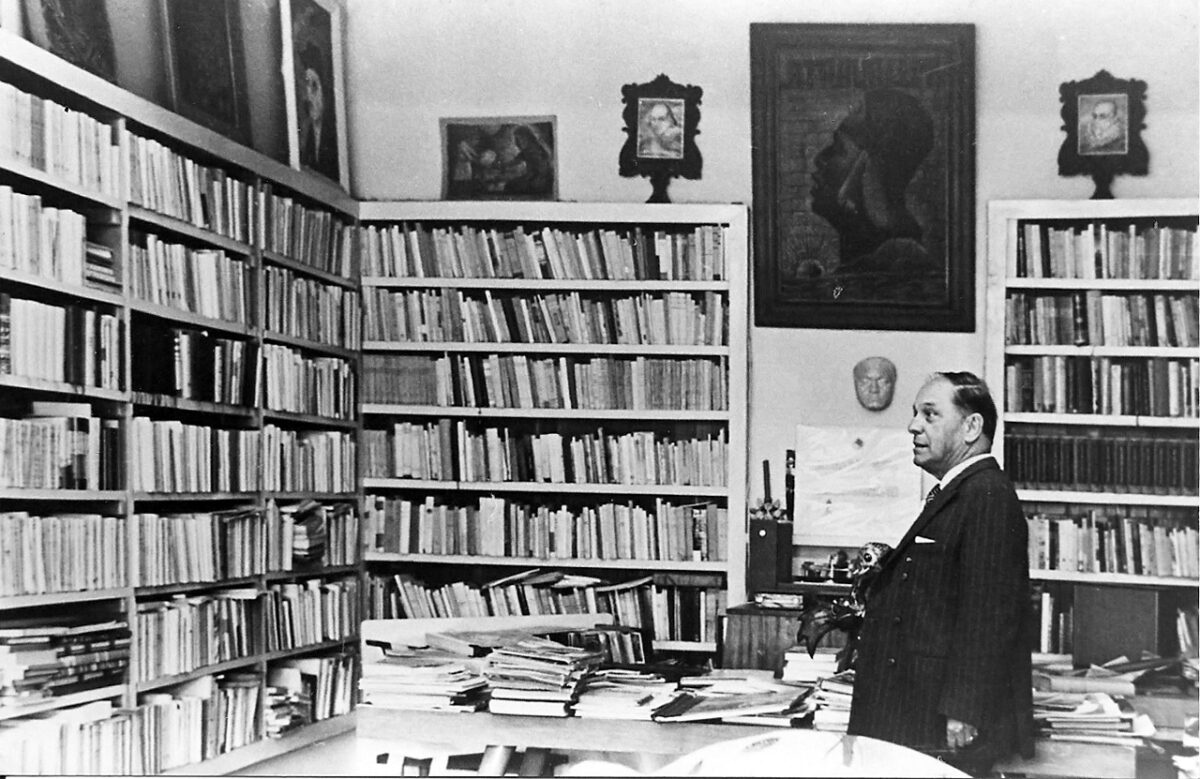

Under Carrión’s leadership, the CCE became a cultural powerhouse. Its headquarters in Quito, inaugurated in 1947, housed several key components of Ecuador’s cultural infrastructure. The CCE established multiple museums, including the National Museum of Ecuador, which showcased the country’s rich archaeological heritage, indigenous art, and colonial history. These museums were designed to foster a sense of pride in Ecuador’s past while also offering a platform for contemporary artists to display their work.

The CCE also created libraries that became central to Ecuador’s intellectual life. These libraries were stocked with works of Ecuadorian authors, as well as important international texts, providing the public with access to a wide range of literary and scholarly materials. In addition, the institution housed performance venues where music, theater, dance, and cinema were regularly featured. These venues were not only spaces for entertainment but also for the education and cultivation of artistic appreciation among Ecuadorians of all backgrounds.

Publishing and Literary Promotion

One of the most significant contributions of the CCE was its role in publishing and promoting Ecuadorian literature. Carrión recognized that Ecuadorian authors and intellectuals needed a platform to reach broader audiences, and he made publishing a central function of the institution. Through the CCE’s printing press, Carrión helped publish numerous works by Ecuadorian authors, many of whom might otherwise have struggled to find a publisher.

The CCE’s publishing arm also issued the influential literary magazine Letras del Ecuador, which became an essential forum for Ecuadorian writers, poets, and intellectuals. Under the editorship of Carrión’s nephew, Alejandro Carrión, and other prominent literary figures, Letras del Ecuador helped promote new voices in Ecuadorian literature and fostered discussions on national identity, culture, and politics. The magazine provided a space for literary innovation, bringing Ecuadorian authors into conversation with global literary trends while also emphasizing Ecuador’s own unique cultural contributions.

Support for Ecuadorian Artists and Intellectuals

One of Carrión’s central goals for the CCE was to provide support for Ecuador’s emerging artists and intellectuals, particularly those from underrepresented or marginalized backgrounds. Under his leadership, the CCE became a vital source of financial and institutional backing for writers, painters, musicians, and scholars. Carrión was particularly keen to promote young talent, and the CCE offered grants, fellowships, and opportunities for young artists to exhibit their work or publish their writing.

The institution also became a hub for cultural exchange. Carrión invited international artists, writers, and intellectuals to visit Ecuador, encouraging dialogue between Ecuadorian creators and their counterparts from Latin America, Europe, and the United States. Figures such as Chilean poet Gabriela Mistral, Cuban writer Jorge Mañach, and Mexican intellectual José Vasconcelos were frequent visitors to the CCE, reinforcing Ecuador’s role as a participant in the broader Latin American cultural renaissance of the 20th century.

Cultural Diplomacy and Ecuadorian Identity

Through the CCE, Carrión sought to elevate Ecuador’s international cultural profile. He believed that by promoting Ecuadorian art and literature abroad, the country could assert itself as an equal participant in global cultural discussions. The CCE organized exhibitions of Ecuadorian art in international venues, published works by Ecuadorian authors in translation, and facilitated cultural exchanges with other countries, particularly in Latin America.

Carrión’s vision for the CCE was intimately tied to his concept of national identity. He saw Ecuador as a “small great nation”—a country that, though modest in size, could achieve greatness through its cultural achievements. By promoting Ecuadorian culture both at home and abroad, Carrión believed that the country could reclaim its dignity after the territorial losses of the 1941 war with Peru and assert itself as a cultural leader in Latin America.

Challenges and Legacy

The establishment and growth of the Casa de la Cultura Ecuatoriana were not without challenges. Carrión faced opposition from conservative political forces and cultural elites who were skeptical of his socialist-leaning, progressive agenda. Financing was often an issue, and Carrión had to fight for government support and funding for the CCE’s projects. Despite these obstacles, he remained committed to his vision, often personally advocating for the institution’s importance to national development.

Carrión’s leadership of the CCE lasted until 1948 and again from 1961 to 1967. Even after stepping down as president, he continued to influence its direction and advocate for its mission. The Casa de la Cultura remains one of Ecuador’s most important cultural institutions, with a legacy that continues to impact the country’s arts and intellectual life.

Lasting Impact on Ecuadorian Culture

The Casa de la Cultura Ecuatoriana played a critical role in shaping modern Ecuadorian identity. Under Carrión’s leadership, the institution not only fostered artistic and intellectual achievements but also helped build a sense of national pride and cultural self-sufficiency. It provided a platform for voices that might otherwise have been silenced or ignored, and it ensured that Ecuador’s cultural heritage was preserved and promoted.

Today, the CCE continues to serve as the beating heart of Ecuador’s cultural scene, with branches across the country and a robust agenda of exhibitions, performances, and publications. Carrión’s vision of a “small great nation” continues to resonate, as the institution remains a symbol of Ecuador’s commitment to culture as a tool for social progress and national unity.

Personal Life

Benjamín Carrión Mora’s personal life was shaped by his strong intellectual upbringing, his family ties, and his deep commitment to both his cultural and political ideals. Born on April 20, 1897, in Loja, Ecuador, Carrión was the youngest of ten children in a prominent family. His father, Manuel Carrión Riofrío, was a literature professor and poet, and his mother, Filomena Mora Bermeo, was an educated woman who played a significant role in Carrión’s intellectual development. After his father’s death in 1903, when Carrión was only six years old, his mother took charge of his early education, introducing him to French literature and fostering his literary interests.

Marriage and Family

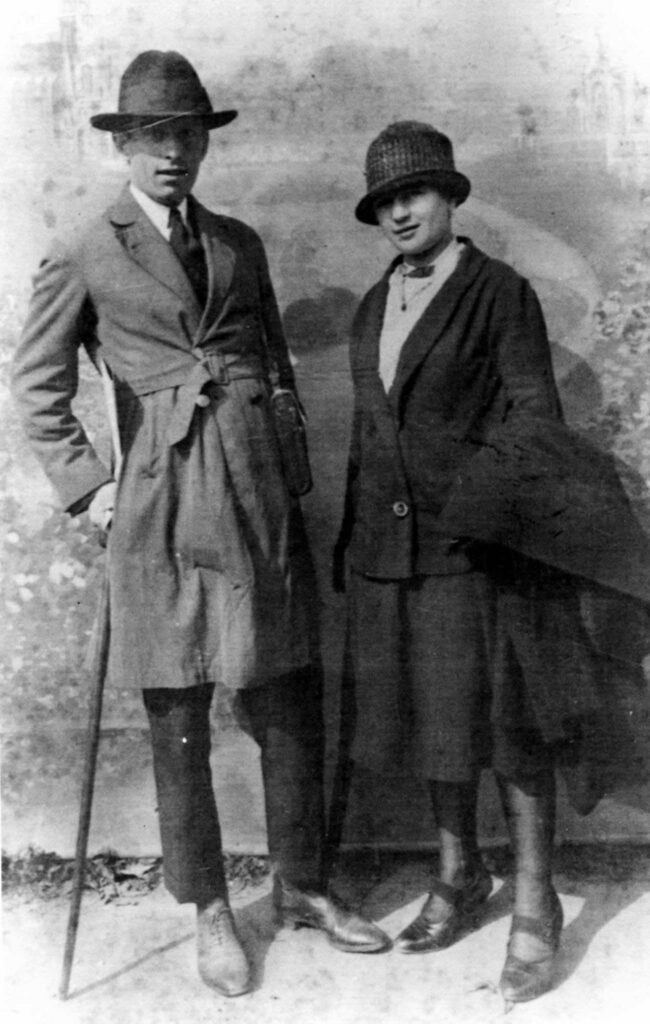

In 1922, Benjamín Carrión married his second cousin, Águeda Eguiguren Riofrío, a woman from another prominent Loja family. At the time of their marriage, Águeda was only 16 years old, while Carrión was 25. The couple had two children, Jaime Rodrigo and María Rosa, whom they affectionately nicknamed “Pepe.”

Carrión’s family life was marked by long periods of separation due to his diplomatic and political duties. For instance, during his consular service in Le Havre, France, in the mid-1920s, Carrión lived abroad with his wife and children. Photographs from the time capture the family during their stay in Bonsecours and Le Havre, showing a man deeply connected to his family despite the demands of his career.

His family was often a source of comfort and inspiration, but like many intellectuals and diplomats, Carrión had to balance the challenges of public life with his private responsibilities. Throughout his diplomatic postings in Europe and Latin America, his wife Águeda and children often traveled with him, particularly during his assignments in Mexico and Chile.

Intellectual and Social Circles

Carrión maintained close friendships with a number of influential intellectuals, artists, and writers, both in Ecuador and abroad. These relationships were not just professional but deeply personal, and they influenced much of his worldview and literary output. His friendship with Gabriela Mistral, whom he met during his diplomatic tenure in Paris, was particularly significant. Mistral wrote the foreword to his first major book, Los Creadores de la Nueva América, and the two maintained a warm correspondence over the years.

His ties to intellectuals extended into Latin America’s artistic circles, where he frequently socialized with figures such as Mexican muralists Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco, and intellectuals like José Vasconcelos. These friendships underscored Carrión’s role not only as a diplomat but also as a cultural ambassador, helping to strengthen Latin American intellectual and cultural solidarity.

Personality and Beliefs

Carrión was known for his intellectual rigor and strong convictions, but those close to him also described him as a warm and approachable figure, deeply committed to the causes he championed. He was passionate about education, culture, and social justice, and these values permeated both his public work and his personal life. His home was often a gathering place for intellectuals, artists, and politicians, where discussions of literature, politics, and culture were common.

Despite his serious intellectual pursuits, Carrión enjoyed everyday pleasures, such as playing chess, a pastime he cultivated throughout his life. His personal papers and photographs show a man who, while deeply invested in Ecuador’s political and cultural future, found joy and solace in his family and intellectual community.

Legacy and Recognition

Benjamín Carrión is regarded as one of the most influential figures in 20th-century Ecuadorian and Latin American intellectual life. His work as a cultural promoter, particularly through the Casa de la Cultura, left a lasting legacy. Carrión’s literary output remains a critical part of Ecuador’s national identity. He received several prestigious awards, including the Benito Juárez Prize (1968) and Ecuador’s highest cultural honor, the Eugenio Espejo Award (1975).

Death

Benjamín Carrión passed away on March 8, 1979, in Quito, Ecuador, at the age of 81. His death came after a prolonged battle with cancer, a condition that had worsened in his final years. Despite his declining health, Carrión remained active in Ecuador’s cultural and intellectual life until his last days, continuing his work at the Casa de la Cultura Ecuatoriana and engaging in public discourse on Ecuador’s national identity and cultural development. His death marked the end of an era for Ecuadorian culture, and he was widely mourned by intellectuals, politicians, and the public alike.

In recognition of his immense contributions to Ecuador’s literary and cultural landscape, tributes and memorials followed his passing. His legacy, particularly the Casa de la Cultura, continued to thrive as a beacon for the arts, helping preserve his vision for a vibrant, united Ecuadorian culture.

Political life

Benjamín Carrión served as the Minister of Public Education, was a vice presidential candidate for the left, and leader of the socialist party. He also served as a diplomat in several European and American countries. Carrión served six years as consul in Le Havre. In 1932 he was elected Secretary General of the Socialist Party.

Personal life

Carrión was married to Águeda Eguiguren Riofrío with whom he had 2 children: Jaime Rodrigo and María Rosa.

Benjamín Carrión‘s Legacy

Pictures with other writers

Awards and recognition

- 1968: Benito Juárez Prize (Mexico)

- 1975: First recipient of the Eugenio Espejo Award, Ecuador’s national prize.

Works

- Los creadores de la nueva América (1928), with a foreword by Gabriela Mistral, read it for free here.

- El desencanto de Miguel García (1928)

- Mapa de América (1931), read it for free here.

- Atahuallpa (1934), read it for free here.

- Índice de la poesía ecuatoriana contemporánea (1937), read it for free here.

- Cartas al Ecuador (1943)

- El nuevo relato ecuatoriano (1951)

- San Miguel de Unamuno (1954), read it for free here.

- Santa Gabriela Mistral (1956), read it for free here.

- García Moreno, el santo del patíbulo (1958)

- Nuevas cartas al Ecuador (1960), read it for free here.

- Por qué Jesús no vuelve (1963), read it for free here.

- El cuento de la patria (1967)

- Raíz y camino de nuestra cultura (1970)

- El libro de los prólogos (1980)

- América dada al diablo (1981)

- Correspondencia de Benjamin Carrión (1995)

Other writers with the last name Carrión

References

- Wikipedia contributors. “Benjamín Carrión.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved on September 24, 2024.

- Carrión, Benjamín. Ecuadorian historian and essayist Benjamín Carrión reading from his work. Library of Congress. Retrieved on September 24, 2024.

- Encyclopedia.com contributors. “Carrión, Manuel Benjamín (1897–1979).” Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved on September 24, 2024.

- Wikipedia contributors. “Benjamín Carrión.” Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre. Retrieved on September 24, 2024.

- Ministerio de Cultura y Patrimonio. “Benjamín Carrión Mora.” Ministerio de Cultura y Patrimonio del Ecuador. Retrieved on September 24, 2024.

- Pérez Pimentel, Rodolfo. “Carrión Mora, Benjamín.” Diccionario Biográfico Ecuador. Retrieved on September 24, 2024.