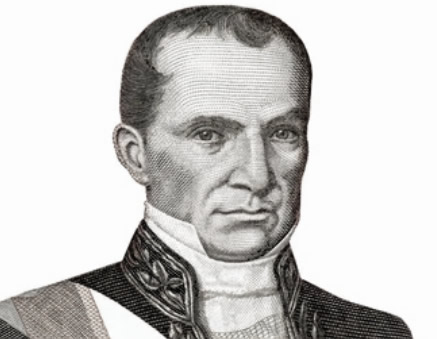

Vicente Rocafuerte Bejarano (Guayaquil, May 1, 1783 – Lima, Peru, May 16, 1847) was an independence leader, statesman, diplomat, politician and writer. He was born into wealth and was educated in Spain. He returned to Ecuador in 1807 and was instrumental in freeing the country from Spain and, subsequently, from Gran Colombia. He served in the National Congress, as governor of Guayas Province, and as the second president of Ecuador (from 1834 to 1839). Rocafuerte’s writings on political systems, social reform, religious toleration, and economic development had significant influence on liberals in several Spanish American nations. Several schools and various awards are named after him, and many statues throughout Ecuador stand in his honor.

Early Life and Education

Vicente Rocafuerte Bejarano was born on May 1, 1783, in Guayaquil, Ecuador, into a wealthy and prominent family with deep connections to both the Spanish aristocracy and the economic elite of colonial Ecuador. His father, Juan Antonio de Rocafuerte y Antolí, originally from Morella, Valencia, in Spain, was a captain in the Spanish Royal Army and had a significant role in the region. His mother, María Josefa Rodríguez de Bejarano y Lavayen, was one of the wealthiest women in Guayaquil, owning vast estates and businesses, including the Naranjito hacienda, which exported cacao, tobacco, and other goods. Rocafuerte was the eighth child in his family and the only surviving male heir, positioning him as the inheritor of the family’s wealth and responsibilities.

In 1793, at the age of 10, Rocafuerte was sent to Europe to receive an elite education. He attended the Colegio de Nobles Americanos in Granada, Spain, and later continued his studies in France at the prestigious Collège de Saint Germain-en-Laye, located near Paris. His time in France coincided with the height of the Enlightenment, and Rocafuerte was exposed to progressive ideas on governance, liberty, and education. His education included military sciences, mathematics, history, and multiple languages, and these subjects deeply influenced his political philosophy and worldview. During this period, Rocafuerte became acquainted with influential figures such as Simón Bolívar and Carlos Montúfar, with whom he developed lifelong relationships.

Political and Diplomatic Beginnings

Rocafuerte returned to Guayaquil in 1807 at the age of 24, taking over the management of the family’s extensive estates, including the Naranjito hacienda. His early foray into politics began in 1810, when he was elected Alcalde Ordinario (city magistrate) of Guayaquil, though his relationship with the royalist governor, Bartolomé Cucalón, was fraught with tension due to their conflicting political views. As a result, Rocafuerte was subject to house arrest in 1810 after being falsely accused of conspiring against the colonial government. Nevertheless, his political influence grew, and in 1812, he was elected as a representative for Guayaquil to the Spanish Cortes in Cádiz, Spain.

In Spain, Rocafuerte was an active participant in the Cádiz Cortes, which was Spain’s attempt to establish a constitutional monarchy. His experience there deepened his belief in liberal constitutionalism and the necessity of reform. However, when King Ferdinand VII dissolved the Cortes in 1814 and restored absolutist rule, Rocafuerte became disillusioned with the Spanish monarchy and began to shift his allegiance toward Latin American independence movements.

Involvement in Latin American Independence Movements

After the dissolution of the Cortes, Rocafuerte embarked on a period of extensive travel across Europe, further developing his political ideas. By 1820, he had become a fervent advocate for Latin American independence, particularly in Mexico and Cuba. Rocafuerte played a significant diplomatic role during this time, helping foster alliances between Latin American independence leaders and European powers.

His time in Mexico from 1820 to 1824 was particularly formative. Rocafuerte became a staunch opponent of the Mexican Empire under Agustín de Iturbide, who had proclaimed himself emperor. Rocafuerte’s writings, including Ideas Necesarias a Todo Pueblo Americano Independiente que Quiere Ser Libre (1821), were instrumental in rallying support for republicanism and constitutional governance, not just in Mexico but across Spanish America. His works advocated for religious tolerance, republicanism, and the protection of individual liberties, gaining recognition throughout Latin America.

During this period, Rocafuerte also served as a diplomat for several newly independent Latin American nations, including Colombia, Mexico, and Cuba. He was involved in efforts to secure European recognition of these new republics and worked on treaties and financial negotiations. From 1824 to 1830, he served as Mexico’s representative to England and other European nations, fostering diplomatic ties and negotiating loans to support Mexico’s fledgling government.

Return to Ecuador and the Presidency (1835–1839)

In 1833, Rocafuerte returned to Ecuador as the nation was in the midst of political turmoil. President Juan José Flores, the first leader of the newly independent Republic of Ecuador, faced opposition from liberal factions. Rocafuerte initially positioned himself as one of Flores’ most vocal critics, advocating for constitutional reforms and opposing Flores’ authoritarian policies. In 1834, Rocafuerte led a rebellion against Flores, but after its defeat, he surprisingly struck a deal with Flores that allowed him to become President of Ecuador in 1835.

As president, Rocafuerte oversaw the drafting of a new constitution, which was adopted in 1835. His presidency was marked by significant reforms, especially in education, governance, and social policy. He emphasized economic liberalization, reduced tariffs, and implemented policies that supported agricultural exports, particularly cacao, which was a cornerstone of Ecuador’s economy. Rocafuerte’s administration also worked to protect indigenous communities from exploitation, particularly in land rights and labor policies.

One of Rocafuerte’s most enduring legacies was his commitment to education. He established secular schools, including institutions for women, which was groundbreaking for the time. Rocafuerte also reformed the prison system and expanded public infrastructure. His efforts to modernize the country included the introduction of steam-powered navigation in the Pacific, and he supported technological advancements in agriculture and industry.

Rocafuerte’s presidency, however, was not without controversy. He often resorted to authoritarian measures to maintain order, including the execution of rebels and political opponents. His strict enforcement of public order and his progressive stance on religious tolerance, which included curbing the power of the Catholic Church, led to tensions with conservative and ecclesiastical authorities.

Later Political Career and Diplomatic Service

After leaving the presidency in 1839, Rocafuerte continued to serve Ecuador in various capacities. He was appointed Governor of Guayas Province, where he focused on expanding infrastructure, including the construction of Guayaquil’s first public docks, a modern customs house, and new transport systems. He also played a pivotal role in fostering international trade by establishing steamship companies that operated in the Pacific, helping to modernize Ecuador’s economy.

In 1845, Rocafuerte became involved in the revolution that ousted Flores from power, aligning himself with Vicente Ramón Roca and the revolutionary government. His participation cemented his legacy as a key figure in Ecuador’s political landscape. Rocafuerte was elected President of the Senate in 1846 and later appointed as a diplomat to Peru, Bolivia, and Chile. His final years were spent in diplomatic service, where he continued to advocate for the interests of Ecuador and fostered regional cooperation.

Personal Life

In 1842, Rocafuerte married Baltazara Calderón Garaycoa, the sister of Ecuadorian revolutionary hero Abdón Calderón. Despite their significant age difference—Rocafuerte was 59 and Baltazara 38—their marriage was reportedly a happy one. The couple had no children, but Baltazara became known for her philanthropic work after Rocafuerte’s death.

Rocafuerte was known for his frugal lifestyle, personal integrity, and deep commitment to public service. Despite his wealth, he lived modestly, devoting much of his resources to public causes and the development of Ecuador. A polymath who spoke several languages, Rocafuerte was known for his intellectual prowess and his deep understanding of both European and Latin American political thought.

Death and Legacy

Vicente Rocafuerte died on May 16, 1847, in Lima, Peru, while serving as Ecuador’s diplomatic representative. He had been suffering from stomach cancer, which had severely weakened him in the months leading up to his death. Rocafuerte’s death marked the end of a career that had spanned the political, diplomatic, and intellectual spheres of both Europe and Latin America.

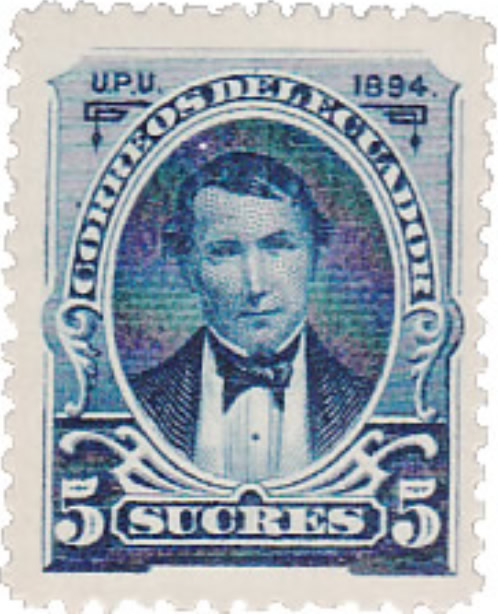

Rocafuerte’s legacy in Ecuador is profound. He is remembered as one of the nation’s founding political leaders and a champion of liberal reform. His contributions to education, governance, and diplomacy continue to shape Ecuadorian society. Numerous institutions bear his name, including the Colegio Nacional Vicente Rocafuerte in Guayaquil, and his ideas on republicanism and religious tolerance influenced liberal thought throughout Latin America.

In recognition of his contributions, Rocafuerte’s remains were repatriated to Ecuador in 1884, and he was reburied in the Catedral Metropolitana de Guayaquil. Today, his final resting place is marked by a mausoleum in the Cementerio General de Guayaquil, where he is honored as a national hero.

Recognition and Influence

Rocafuerte’s writings, such as Ideas Necesarias a Todo Pueblo Americano Independiente and Ensayos sobre la Tolerancia Religiosa, are still studied as foundational texts in Latin American political theory. His efforts to modernize Ecuador and his advocacy for republicanism, social reform, and religious tolerance have cemented his place in history as a visionary leader. In modern Ecuador, awards such as the “Gran Cruz Vicente Rocafuerte al Mérito Diplomático” honor individuals for excellence in diplomacy, a fitting tribute to a man whose life was dedicated to both his nation and the broader cause of Latin American independence and unity.

Monuments and Honors Dedicated to Vicente Rocafuerte

Selected works

- Ensayo Sobre Tolerancia Religiosa (1831)

- Ideas Necesarias A Todo Pueblo Americano Independiente: Que Quiera Ser Libre (1821)

- Bosquejo Ligerísimo de la Revolución de Mégico, Desde el Grito de Iguala Hasta la Proclamación Imperial de Iturbide

- Ensayo Politico: El Sistema Colombiano, Popular, Electivo, Y Representantivo, Es El Que Mas Conviene A La America Independiente (1823)

- Defensa Documentada De La Política Del Señor D. Vicente Rocafuerte Durante Un Juicio Relativo Á Las Atroces Calumnias Que Publicó Contra Su Memoria El … Fallo Definitivo Del Poder.

- Memoria politico-instructiva, enviada desde Filadelfia en Agosto de 1821, a los gefes independientes del Anáhuac, llamado por los españoles Nueva-España.

- Testamento de Vicente Rocafuerte (1847), read it for free here.

- Ensayo sobre el nuevo sistema de carceles (1830), read it for free here.

References

- “Rocafuerte, Vicente (1783–1847).” Encyclopedia.com. Available at: https://www.encyclopedia.com/humanities/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/rocafuerte-vicente-1783-1847

- “Vicente Rocafuerte.” Wikipedia, La enciclopedia libre. Available at: https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vicente_Rocafuerte

- “Vicente Rocafuerte Rodríguez de Bejarano.” Real Academia de la Historia – Diccionario Biográfico Español. Available at: https://dbe.rah.es/biografias/52074/vicente-rocafuerte-rodriguez-de-bejarano

- “Vicente Rocafuerte.” Enciclopedia del Ecuador. Available at: https://www.enciclopediadelecuador.com/vicente-rocafuerte/

- “Rocafuerte Vicente y Bejarano.” Rodolfo Pérez Pimentel. Available at: https://rodolfoperezpimentel.com/rocafuerte-vicente-y-bejarano/